Also see the brief description of the book by the publishers and the book review from Burlington Magazine.

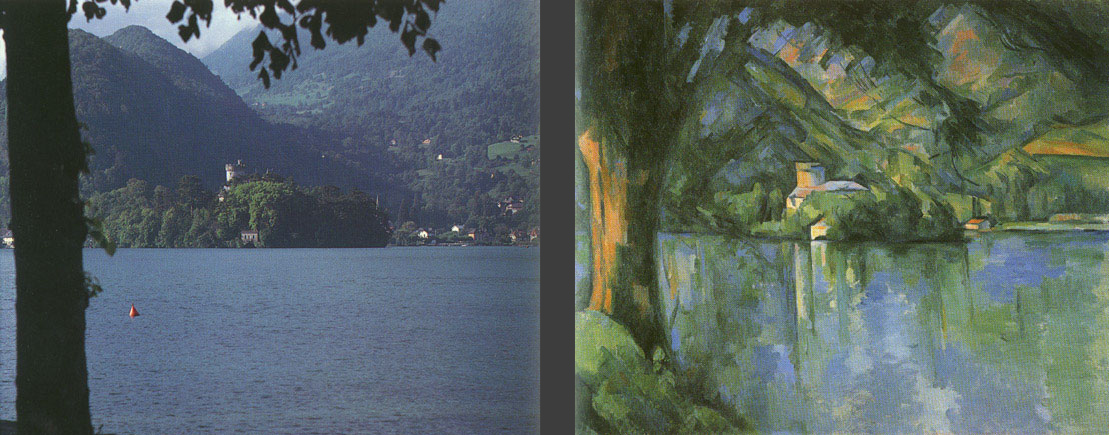

Le Lac d'Annecy

Fig 59, Fig 60

As powerfully as Cézanne can endow inanimate form with bodily rhythms, his more typical preference is to avoid all the anecdotal suggestion that a motif impose upon the casual observer. Suggestive in just such a manner is a motif one can see from the terrace of a lakeside botel near where he vacationed with his wife in 1896 (Fig. 60). The countryside was unfamiliar to him: alpine, dark blue-green, a haven for wealthy tourists. He was aware of its ordinary appeal: "it is still nature, of course, but a little bit as we have learned to see it in the travel sketchbooks of young ladies."10 The château has a peculiarity that strikes even an unsentimental eye immediately -- the boathouse, whose windows and landing dock look like a face submerged in the water down to its gaping mouth. No part of that suggestion is taken up by Cézanne. He leaves the boathouse wall blank and incorporate roof into the angles of the château roofs; he inserts those in turn into the system of diagonals by which the whole upper half of the canvas is animated. He rests upper half on a stable base constructed of vertical and horizontal touches, and connects the two parts by the deep reflections and the tree at the left.

The blue-green local hue receives its "resonant compass" from division into its components, blue and green. Conceived as separate, the two colors permit a closer integration of the canvas surface: the green patches in the water incorporate the smooth lake into the mosaic of the hills. But the compass is made to resonate even more deeply by the addition of warm pinks, pink-violets, and ochres.

Cézanne's late style is adumbrated here in part by the tight interlocking of the color abstractions, in part by the very positive painting. In work that comes later, the color patches take different forms: there are diagonally placed patches with sharp upper outlines which overlap emphatically (Forêt, Fig. 133); long, stringy forms composed of vertical touches that lie flat (L'Église de Montigny-sur-Loing, Fig. 135); and stubby, detached patches which barely interlock (Le Jardin des Lauves V. 1610). The touches in this painting are not at that level of abstraction, yet their close integration, broad color range, and affirmative use, are typically late.

Rochers à l'Estaque

Fig 27, Fig 28

It is perhaps the interplay between Cézanne's close attention to the motif and his power of synthesis that strikes the deepest chord. The structure of the solid forms is defined by the motif, while the treatment of the surfaces is shaped, again, by Cézanne's compositional purpose. Painters speak of making a painting "work," and by this they refer to the adjustments that must be made -- sometimes right away, at other times back in the studio -- in order to balance space, shape, and color. Cézanne apparently felt the need to correct the composition for rightward tilt, and must have made two adjustments on the spot: he reduced the size of the rocks in the upper right corner and tilted the horizon to the left. He made several other decisions, all for the sake of balance or clarity, which he could have carried out at any time. For greater clarity and rhythm, he emphasized the correspondence between the distant horizon and the line of hills just below, and even reversed the direction of light on the solitary house so that we might see it better and note its relation to the rock above. Subtly and systematically, he painted the sloping hillside -- which seems to run unchecked toward the lower right -- with parallel touches oriented at right angles to the slope, in this way slowing down the recession and providing a counterbalancing diagonal movement. For stability, he rendered the central rock with stable, vertical strokes.

L'Église Saint Pierre à Avon

A painter freed from the constraints of his imagination -- to reverse the more common metaphor -- has an infinity of visual realities to explore. Cézanne's were for the most part complex and subtle; in oil paintings he usually combined the curvilinear and linear, the soft and the hard. In his pencil drawings and watercolors he was free to explore riskier arrangements, however, and the result could be more one-sided. In L'Église Saint Pierre à Avon (Fig. 54), for example, he explored the interrelations among straight edges and surfaces. Except for the whole right side of the street, which has been demolished, the motif has remained unchanged; we can see from Cézanne's viewpoint the entire tenth-century portal. Although it intrudes into our comparison, it is a beautiful Romanesque construction in its own right. Cézanne saw the extraordinary interplay of diagonals and for obvious compositional reasons chose not to flatten any of those that recede in space. It is testimony to his vision -- and that of painters in general, although anyone's capacity -- that, when he needed to, he could see sharply receding horizontal edges as lines that function as diagonals in the plane of the paper. The normal tendency is to see them three-dimensionally, therefore as closer to factual horizontal. As soon as they are perceived as flat projections, they can complement and extend the world of diagonals in the facade of the church: a world worth exploring, one may feel, though here perhaps excessively ordered. Once the diagonals had been properly located on the surface, Cézanne could attend to depth in the details. Simply by recording shadows he gave us a precise feel for the hollows, the overlappings, and the convexities of the architecture. By ignoring the color of the roofs, he made us attend to the manner in which the building is built upwards and outwards.

Fig 53, Fig 54

10) Letter of July 21, 1896.

Brief description : CÉZANNE Landscape into Art by Pavel Machotka.

Designed by Gillian Malpass, Yale University Press. Released February 7, 1996

- Lavishly illustrated with more than 100 colorplates

- An exhibition on Cézanne, called by the New York Times "the hot new artist of the '90s," will be shown at the Philadelphia Museum of Art from May 25 to August 18

This beautiful book presents a new perspective on Paul Cézanne, one of the towering figures of nineteenth-century art. Pavel Machotka has photographed the sites of Cézanne's landscape paintings--whenever possible from the same spot and at the same time of day that Cézanne painted the scenes. Juxtaposing these color photographs with reproductions of the paintings, he offers a dazzling range of evidence to investigate how the great painter transformed nature into works of art.

Machotka, himself an artist, moves from painting to painting, examining textures and surfaces, pictorial rhythms, and inflections of tone. As he analyzes Cézanne's treatment of individual sites, their transposition into forms and colors, and the artist's responsiveness to the demands of each unique composition, we begin to see Cézanne as he saw himself: not as an early Cubist but as a painter who explored his motif for its rich compositional potential and presented a parallel and faithful conception of it. Using color to define form, while retaining hues that are anchored in reality, Cézanne achieved sensuous reconstructions rather than intellectual depictions like those of the Cubists.

While there are other books on Cézanne's landscapes, none is as closely informed by painterly knowledge and perception or as complete in its grasp of Cézanne's period and geography as this one. A visual delight, it is also an illuminating and original interaction with the artist's work.

Pavel Machotka is professor of psychology and art at the University of California, Santa Cruz. He has exhibited his own paintings at the Campbell-Thibaud Gallery in San Francisco and at other galleries, and his work was recently featured and reviewed in American Artist.

Reproduced from the Yale Spring 1996 catalog with permission.

Book review, The Burlington Magazine, September 1996

Of the many publications issued to coincide with the recent Cézanne retrospective, one immediately takes its place as an indispensable work on the artist. As its title suggests, Pavel Machotka's Cézanne, Landscape into Art is an investigation of the relationship between Cézanne's landscape motifs and his paintings of them, which consists of a host of new photographs of the artist's sites and, for this alone, constitutes an invaluable addition to our knowledge. More notable than this, however, are the masterly powers of analysis and interpretation that Machotka brings to this material. These explore all aspects of Cézanne's complex dialogue with art and nature - or construction and vision - with a subtlety and insight that constantly remind us that the author is not only a professor of psychology and art but also (like Gowing before him) a practising painter.

For the scholar already familiar with Cézanne's art, the chief revelation of this volume will be the sudden encounter with a wealth of newly identified sites, the majority of them photographed at the same time of day and season of the year as Cézanne's paintings of them - an astonishing testimony to the author's tenacity and resourcefulness in the precarious pursuit of motif-hunting. Here, for the first time, L'Église de village (V. 1531) becomes L'Église de Montiglly-sur-Loing (Figs. 47 and 48) and is dated 1904-05 (rather than l900-04) on the basis of Cézanne's known movements. Other surprises include a photograph of the exact site of the Toledo Allée à Chantilly (V. 627), the Courtauld's wondrous Lac d'Annecy and the water-colours of Le Château de Fonlainlebleau (R. 628) and Une rue à Aix (R. 327), which Machotka has now identified as L'Église Saint-Pierre à Avon. Given the amount of transformation that any landscape site is likely to have undergone in the century since Cézanne confronted it, it is little short of miraculous that so many of his motifs survive so relatively unscathed by the industrial 'progress' that the artist himself so deplored.

Though Rewald and Marschutz published photographs of Cézanne's sites as early as the 1930s, it was only with the appearance Erle Loran's Cézanne's Composition in 1943 that a wide variety of them became available for the general reader. Inevitably, Machotka is forced to rely upon certain of these in cases where Cézanne's motifs are no longer recognisable. In his examination of this evidence, however, he differs radically from Loran and rightly affirms Cézanne's position as the last great painter to work from - rather than merely with - nature.

When Loran wrote, Cézanne was venerated above all as the precursor of Cubism and, by extension, the father of modern art. This was reflected in Loran's own analyses of Cézanne's compositional practices, which repeatedly stressed the degree of spatial distortion and formal manipulation the artist exercised over his subjects, as though already foreshadowing Braque's goal of 'fighting the habit of painting before the motif'. What Machotka succeeds in doing, however, is in restoring 'the primacy of perception' to Cézanne's landscape paintings. While conceding that the artist often made adjustments to his motifs to enhance the unity and aesthetic integrity of his canvases, Machotka reminds us of the even more complex strategies that Cézanne employed in order to ensure that he remained essentially faithful to his subjects when transforming them into a picture.

One of these was his very choice of site and his preferred viewing angle: frontal, central, avoiding strong receding diagonals and favouring, instead, prevailing horizontals and verticals. (In this regard, there is no more revealing photographic comparison in Machotka's book than that between two views of a rocky ridge at the Château Noir, both taken from the same spot, one precipitously imbalanced and the other already recommending itself as ordered, stable, and self-contained enough to warrant the artist's attention.) Others include the prevailing colour harmonies ol the motif and the extent to which these were modified by changing atmospheric conditions. As Machotka acknowledges, careful judgment of all of these often determined the sucecss or failure of one of the artist's landscape compositions. Where Cézanne found these wanting, he introduced subtle modifications of structure or tonality that served better the needs of his picture. Viewed alongside photographs of the motifs, however, these constitute minor alterations intendedd to remind us that the artist never remained tyrannised by his subjects; as Cézanne himself confessed, 'art is a harmony which runs parallel with nature'.

There is little with which to take issue in this rich and inspiring volume, though one might have wished for a few more photographs of sites that Cézanne rejected; and, to this reviewer at least, the date of c.l898 assigned to La Sainte-Victoire vue des Infernets (V. 664) seems six to eight years too late. Otherwise, Machotka is unfailingly astute. In illuminating 'asides' on the problems posed by the artist's early subject pictures or on the emotional crisis he experienced in 1885-86 - when he wilfully sought a degree of compositional certainty in his landscape subjects (so lacking in his life) - the author reveals a sympathy and understanding of his subject that are rarely to be found in more straightforward monographs. For all of these reasons, this beautifully produced and handsomely illustrated volume is essential reading for the Cézanne enthusiast. One can only hope that Machotka will now turn his attentions towards a more all-embracing account of the artist's achievement.